ALCOHOL AWARENESS WEEK 2020: SUPPORTING PEOPLE IN RECOVERY

This week is Alcohol Awareness Week and this year’s theme is Alcohol & Mental Health. At People’s Voice Media, we’re taking the opportunity to reflect on work we’ve carried out with people with alcohol addictions, and the learnings we’ve made to help services better support those on the road to recovery.

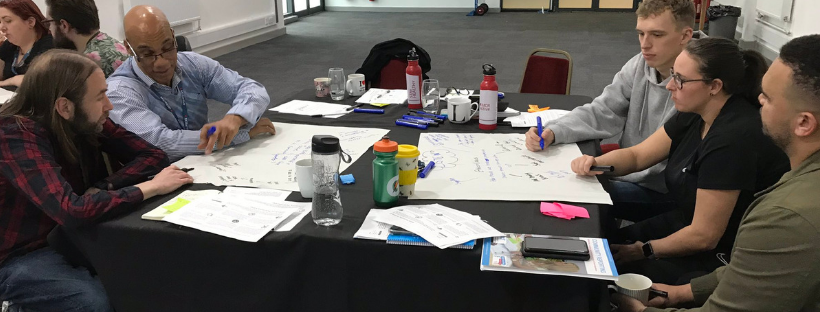

In the course of our work, we’ve gathered stories from people recovering from alcohol addiction, with the discussion particularly focused on the process of recovery: what recovery means to them, the support available, what works, and what doesn’t.

Throughout our chats, the idea that kept coming up was that recovery was akin to going on a journey, to being reborn. Recovery isn’t a quick fix, or a cure, but rather a hopeful journey that takes the person experiencing it to a new way of living.

We also uncovered a variety of learnings about why some recovery services work better than others, and what people living with addictions would like to see from the services supporting them.

- Recovery is not a box-ticking exercise and what works for one person won’t necessarily work for another. It’s a non-linear journey so a one-size-fits-all approach is not going to work.

You know, many years ago, if you couldn’t attend an appointment then you’d be sent a letter, you know, you’ve missed your appointment, you’ve missed your appointment, we’re closing your file. But now, you know, we’re evolving where we can we will come and see you and work around the client.” He goes on to say that this change in delivery is brilliant.

Person in recovery

- While some people with addictions will have shared experiences, this does not mean they have the same experiences. So, while some aspects of recovery, such as detox and rehab, are standard, a person-centred approach needs to be taken in order for each individual’s circumstances to be taken into account.

- Recovery does not happen in isolation. Each person has their own recovery community that can include Recovery Workers, care workers, social workers, medical professionals, family and friends. The more people supporting the service user, the more tailored their recovery journey can be. And the less isolated the person in recovery is, the more their recovery is likely to succeed.

I don’t know where I’d be if it wasn’t for the support networks. I don’t believe I’d be here now at all, and I’m very, very grateful.

Person in recovery

- If more people are involved in an individual’s recovery, then less pressure is on the Recovery Worker since they are not the only source of support for that person and this, in turn, means that they are able to help service users more effectively and take care of their own wellbeing.

Ultimately, the biggest learning to come out of the stories we gathered is that people should be treated as more than just their addiction in order to support their recovery from it.

For more information on how you can get involved in Alcohol Awareness Week, visit Alcohol Change UK.